The program to translate names into numbers and vice versa is called, “DNS,” or Domain Name System, and computers that run DNS are called, “DNS servers.” Without DNS, we’d have to remember the IP address of any server we wanted to connect to – no fun.

The program to translate names into numbers and vice versa is called, “DNS,” or Domain Name System, and computers that run DNS are called, “DNS servers.” Without DNS, we’d have to remember the IP address of any server we wanted to connect to – no fun.

DNS is such an integral part of the internet that it’s important to understand how it works.

Think of DNS like a phone book, but instead of mapping people’s names to their street address, the phone book maps computer names to IP addresses. Each mapping is called a “DNS record.”

The internet has a lot of computers, so it doesn’t make sense to put all the records in one big book. Instead, DNS is organized into smaller books, or domains. Domains can be very large, so they are further organized into smaller books, called, “zones.” No single DNS server stores all the books – that would be impractical.

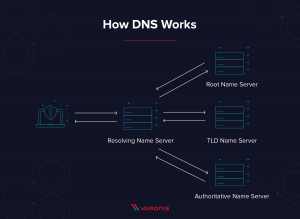

Instead, there are lots of DNS servers that store all the DNS records for the internet. Any computer that wants to know a number or a name can ask their DNS server, and their DNS server knows how to ask – or query – other DNS servers when they need a record. When a DNS server queries other DNS servers, it’s making an “upstream” query. Queries for a domain can go “upstream” until they lead back to domain’s authority, or “authoritative name server.”

An authoritative name server is where administrators manage server names and IP addresses for their domains. Whenever a DNS administrator wants to add, change or delete a server name or an IP address, they make a change on their authoritative DNS server (sometimes called a “master DNS server”). There are also “slave” DNS servers; these DNS servers hold copies of the DNS records for their zones and domains.